In The Atlantic today, David Frum records perhaps the first gunshot in deepfake campaigning:

And then, at 8:25:50 pm ET, the president retweeted an account he had never retweeted before. The account had posted a video of former Vice President Joe Biden, crudely and obviously manipulated to show him twitching his eyebrows and lolling his tongue. The caption read: “Sloppy Joe is trending. I wonder if it’s because of this. You can tell it’s a deep fake because Jill Biden isn’t covering for him.”

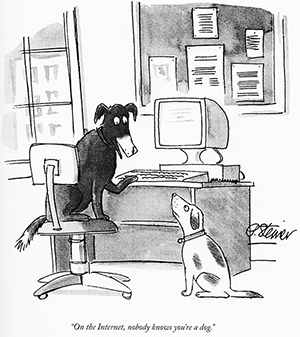

As I’ve written here before, deepfake videos are emerging as a new form of political rhetoric. With technological wizardry now available to anyone with a Verizon bill, our visual political commentary is shifting from the ubiquitous political cartoon to the imagery of digital caricature—from the opinion page to the viral tweet. And the ubiquity of the ink pen, an earlier era’s weapon for political cartooning, now competes with the ubiquity of the smartphone processor. Jacob Schulz at Lawfare:

Deepfake creation used to require a serious computer and a good baseline of technological skill. But that barrier to entry has begun to erode. iPhone deepfake apps have arrived, and they’ve made creating deceptive media easier than ever. An iPhone-created deepfake tweeted by an anonymous user with only 60,000 followers received a presidential retweet within an hour of posting. The era of the deepfake apps has arrived.

Schulz writes that deepfake technology is “unlikely to sway the 2020 election.” Instead, he sees a more imminent danger in “cheap fakes—more rudimentarily edited deceptive videos—and clips that simply remove the underlying context of a politician’s comments,” for example a May 2019 video of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi that slowed her speech to give the impression of drunkenness. (Pelosi, like Trump, is a teetotaler.) I hope he’s correct. But even if deepfakes don’t demonstrably sway the current election cycle, their increasing proliferation in the months ahead promises what Frum calls “an experimental test of the rules of social media.” He continues: “Because the account retweeted by Trump explicitly labels its video a ‘deep fake,’ it arguably does not violate Twitter’s anti-deception policy.” Are caricatures like the one in Frum’s essay mere fiction or outright deception? Worthy of a take-down request or protected by the principles of free artistic expression? These questions, of course, bear not merely on literary considerations of forgery and impersonation but also on legal matters like libel.

In his foundational Handbuch der literarischen Rhetorik, Heinrich Lausberg observes that caricature “need not be historically true—it must only be probable” (§821). As the genre of the political video clip slips from documentary evidence to creative fabrication, the language of probability will displace the language of fact and evidence. That’s my prediction, for what it’s worth. Another, to boot: Schulz may be right that deepfakes are not likely to sway 2020, but let’s remind ourselves that 2024 begins mid-November.